Abortion rights have always been a controversial topic, especially in the US. The fight to secure them has always been an uphill battle, thanks to the numerous colossal anti-abortion groups in existence. Many of these groups have embedded themselves deep within the US legal system, making it preemptively biased against any argument in favor of abortion. The road to the current state of abortion rights is long and has a rollercoaster-like pattern of victories and defeats. But each of them has subtextual and contextual elements that build a picture of the larger societal problems of neglect and control, as well as the system of protections put in place to combat these issues. And while this whole conflict started quite some time ago, the battle rages on today, more ferocious and intense than ever.

The backstory (1965-1973)

Before diving into the most well-known abortion rights case and the decades of legal cases clarifying a heap of specific questions surrounding it, it’s important to set up what the landscape of women’s reproductive rights looked like beforehand.

Griswold v. Connecticut

One of the first cases that led to a larger discussion of reproductive rights on a federal level is Griswold v. Connecticut (1965). The case itself focused on the delivery of information and advice to a married couple about contraceptive measures, as well as the prescription of a contraceptive for the wife’s use. This went against a state statute that prohibited any person from using any type of contraceptive device or drug. The court case decided that a law restricting or prohibiting the usage of contraceptives amongst married individuals was unconstitutional. The argument was that it went against the Fourteenth Amendment, which entailed the right to marital privacy.

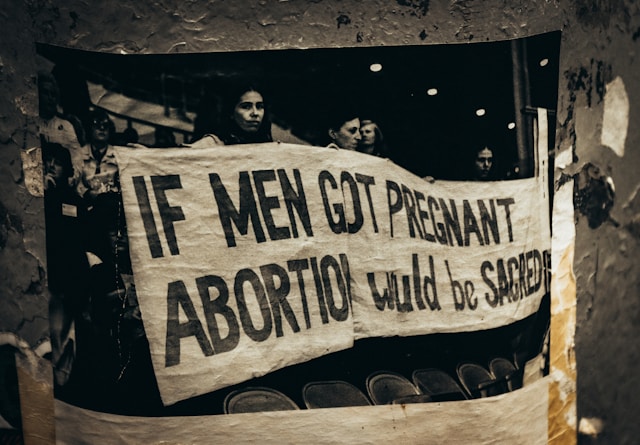

While there isn’t a direct connection to abortion in the case, the focus on a woman’s right not to have children is a related factor. In this case, the right pertains to the initial decision of not developing pregnancy at any stage, in contrast to the right to terminate a pregnancy that is already developing. The presence of a law essentially forbidding a woman from choosing not to become pregnant at all hints towards an innate power that the law gives to men over women. The only way that a woman could avoid becoming pregnant with a law like this in play would be if any man she was in a relationship with also didn’t desire children, or sex in general.

This court case establishes a thin protective barrier around the reproductive rights of women. However, the barrier requirement of marriage naturally excludes a large portion of women from this protection, leaving room for improvement.

Eisenstadt v. Baird

This massive oversight was addressed in the case of Eisenstadt v. Baird (1972), which involved a professor giving out contraceptive foam at the end of one of his lectures on contraception. This went against a Massachusetts law that prohibited the giving away of a contraceptive unless under certain conditions: a registered physician prescribing or administering one to a married individual, or a registered pharmacist acting on said prescription to a married individual. The case ended in the judgment that a law restricting access to contraceptives for unmarried individuals, when it allowed the same access to married individuals, conflicted with the equal protection clause found within the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution.

This case expanded that protective shield around reproductive rights that Griswold v. Connecticut introduced, making marriage no longer a requirement. The fact that the lack of marriage acted as a roadblock to contraceptive options for women builds upon the assumed power men are given under the law. Without marriage, an institution that historically signed away many of the wife’s rights over to the husband, the same lack of choice in pregnancy would apply to this situation as it did in the previous scenario. While the past two cases have been a great step forward, not all legal cases lead to progress.

Doe v. Bolton

Essentially, the sister case to Roe v. Wade, Doe v. Bolton (1973), was tried at the same time alongside it. The law examined stated that abortion in Georgia was only legal when performed by a licensed Georgia physician, on a Georgia resident, and only under these conditions: the pregnancy endangers the pregnant woman’s life or general health, the child would be born with a severe, debilitating physical condition, or the pregnancy was caused by rape. The main point of contention in the lawsuit was that this procedure was only allowed if the physician deemed it so under “his best clinical judgment.” The case argued that “his best clinical judgment” was too vague. Unfortunately, the court found this untrue and judged accordingly.

While the weight given to the “best clinical judgment” of the physician also underlines the lack of power women have in the legal system (especially with the language asserting a “he” in the role of the physician), the sheer amount of requirements necessary for the procedure to even be considered is also staggering. A law like this turns the option to get an abortion for women into a steep uphill battle. The restriction is that the pregnancy itself must also be in some way traumatic or harmful to the woman or fetus, and not that the woman simply doesn’t want the pregnancy, further demonstrating the lack of control women experience over their reproductive rights.

The foundation (1973)

As the most well-known case in relation to abortion rights, Roe v. Wade (1973) established the foundational framework for most of the other cases related to abortion rights, built on or clarified. It came as a result of when a Texas woman became pregnant with her third child, and didn’t want to give birth. At the time, an abortion was only legal in Texas if it could help prevent suffering or death of the mother. She had falsely claimed that she had been raped to build a case for getting an abortion. She also attempted to get an illegal abortion.

Neither of these attempts was successful, and she eventually gave birth to her third child against her wishes. The judgment decided at the end of the case set a federal standard that a woman may receive an abortion if the fetus has not yet reached “viability” (ability to live outside the womb, which usually happens around 24-28 weeks of pregnancy). However, this does not fully negate a state’s individual laws after the point of “viability” has been reached.

The safety net

The decision reached in Roe v. Wade created a strong safety net for all women seeking an abortion in the earlier stages of pregnancy. Of course, those who desired one beyond the period of “viability” were at the mercy of the state’s laws regarding the matter. While the safety net is great, its exclusivity to those who act earlier rather than later has the potential to create a sense of panic and decision paralysis. They might struggle with feelings of both wanting to decide on an abortion as early as possible to avoid entering the “viability” period, and wanting time to prepare emotionally and mentally for the procedure.

Their ability to fully explore and decide whether or not they want to go through with the abortion may also be affected by the presence of a stressful time limit, no matter what their final decision is. While the decision of Roe v. Wade was only a partial victory, most of the cases centered on abortion in the US appear to be answers to questions left over by the vague nature of the broad terms defined by it.

The tug of war (1976-2016)

While the other cases before now have been examined in detail and in order, the following ones will look more into how they modified and attempted to expand (or, in some cases, shrink) the safety net that Roe v. Wade created. Between the years 1976 and 2016, there was a roughly even amount of steps forward and back in securing better abortion rights for women. A legal game of tug of war ensued between those fighting for and against better rights in these two and a half decades.

Progressive cases

The cases that resulted in a further expansion and strengthening of this net include Planned Parenthood v. Danforth (1976), Hodgson v. Minnesota (1990), Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pa. v. Casey (1992), Stenberg v. Carhart (2000), and Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt (2016).

Parenthood v. Danforth

Parenthood v. Danforth decided that a state couldn’t constitutionally require the permission of the spouse of a pregnant woman for an abortion, but only up to her first trimester of pregnancy. It was reasoned that if a state wasn’t allowed the power to forbid abortion under the same set of circumstances, then a spouse wouldn’t constitutionally have that power either.

Hodgson v. Minnesota

Hodgson v. Minnesota clarified that a pregnant minor couldn’t be expected to require the permission of both their parents for an abortion. They found this requirement counterintuitive to the protection of pregnant minors or familial integrity, as it had the potential for degradation of communication within a family, and possibly even increasing the likelihood of domestic violence.

Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pa. v. Casey

Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pa. v. Casey made it illegal for states to create laws that put significant barriers for women seeking an abortion of a fetus before “viability.” It found favor in using a more empathetic “undue burden” standard when judging the legality of an abortion, believing that harsh, intentionally antagonistic scrutiny of the legitimacy of an abortion’s “necessity” was unhelpful and unfair. Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt reinforced this finding, stating that the state couldn’t require the presence of a physician who has administrative privileges of a hospital close to the abortion clinic. They also forbid the requirement of abortion clinics to meet the state’s minimum standards for Ambulatory Surgical Centers (ASCs). The court found that these potential requirements didn’t protect women’s health any more effectively than other laws did.

Stenberg v. Carhart

Stenberg v. Carhart made it mandatory for any state’s anti-abortion laws to include an exception for any scenario that would impact the mother’s health. A state also couldn’t pass a law forbidding partial-birth abortions without making a clear and full distinction that the law doesn’t extend to any other type of abortion. The court found both conceptual laws contradictory to the Fourteenth Amendment.

Looking deeper

The first two progressive cases appear to focus on the potential familial barriers and conflicts related to abortion. They seem to disavow the unfounded “right” for others within a pregnant woman’s life to have any, or at least a majority of, control over her own body. It puts the patriarchal idea of male power over women in the crosshairs, stating that those in the traditional roles of “husband” and “father” could not be the end-all-be-all dissension makers in these cases. In fact, they both hint that this societal standard had a severe negative effect on both the safety of the pregnant women and tended to decay the “family values” that they attempted to protect in the first place.

The latter three cases strongly lambast the reckless and unsympathetic nature of many states’ laws regarding abortion. The two make it clear that the disregard for women’s health and quality of life was an inexcusable situation. They argued that these types of state laws were unarguably cruel, as they serve no other purpose than to make the lives of these women seeking an abortion as difficult and painful as possible, while also increasing the likelihood of pregnancy-related deaths and life-long injuries by an uncountable number.

Regressive cases

Cases that ended in the shrinking or weakening of this abortion safety net are as follows: Maher v. Roe (1977), Harris v. McRae (1980), Webster v. Reproductive Health Services (1989), and Gonzales v. Carhart (2007).

Maher v. Roe

Maher v. Roe and Harris v. McRae both denied any requirement for the medical financial aid by a state for abortions, unless the abortion was deemed medically necessary. The argument had been made that if a state has the legal requirement to cover childbirth expenses financially through medical insurance under the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, then the same should apply to abortion expenses. However, the court disagreed with this comparison, finding the matters unrelated, stating that the presence of financial need was not enough of a reason for guaranteed financial aid. Harris v. McRae, in particular, also claimed that poverty was outside of the state’s control, thus not a barrier that the state is required to remove or address, despite the protection of “liberty” in the Due Process Clause of the Fifth Amendment.

Webster v. Reproductive Health Services

Webster v. Reproductive Health Services denied any contradictions to the court’s previous finding with a law that restricts the use of public areas, and the employees of said areas, in performing or assisting in abortions that weren’t medically beneficial. The court also denied the presence of a guarantee of governmental aid within the Due Process Clause of the Fifth Amendment, despite the restriction of aid potentially leading to the lack of protection of an individual’s rights to secure life, liberty, and/or property as stated within the clause.

Gonzales v. Carhart

Gonzales v. Carhart set a precedent that a state may bar or substitute certain procedures as long as these actions aren’t seen as imposing an undue burden. This especially applies in the case of partial birth-abortions, which the court decided had ethical and moral elements not present in other forms of abortion. These ethical and moral elements, the court argued, made the law non-contradictory to the Fourteenth Amendment.

What went wrong?

All these cases have shared elements of contradiction and hypocrisy strewn throughout them. They all involve the court having to dance around the Fifth Amendment and Fourteenth Amendment, trying their best to find a loophole out of actually following through with what those amendments guarantee. Many of them focus quite heavily on the denial of financial assistance with the procedure, massively underselling the reality of poverty as an undo barrier in large portions of society, much less regarding women’s abortion rights. The passionate lengths and effort the courts put into carving out abortion from access to the same resources that other medical procedures are given without hesitation highlights an undeniable double standard.

While the forty years of legal cases summarized in this section show a general balance between progressive and regressive movements made by the courts, the cases present in the following years up until now follow a trend of constant regression, leading up to the ultimate removal of the safety net Roe v. Wade had created in the first place.

The freefall (2022 – 2025)

After 2016, the road to securing abortion rights has gone drastically downhill. Since 2016, the only three federal cases regarding abortion have been Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization (2022), FDA v. Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine (2024), and Medina v. Planned Parenthood South Atlantic (2025). Two of the three cases that bookend this trio have been focused mainly on the deempowering, if not total removal, of a majority of the progress made for abortion rights for women in US legal history. The middle case was one of the only glimmers of much-needed hope in this dark time. The first measure taken in this crusade was the destruction of the abortion rights foundation itself.

Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization

Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization overturns Roe v. Wade and Planned Parenthood of Pennsylvania v. Casey, stating that states should have the right to individually decide their own status regarding limiting or banning abortion. The court claimed that the analysis presented in Roe v. Wade was flawed in some manner, and that considering abortion an autonomous right would also invite things like drug use and prostitution as potential autonomous rights.

The strange focus the court puts on the strictness of what could be considered an “autonomous right” makes the male-centric power of the law rear its ugly head back into the conversation. If a woman doesn’t have the rights to her own body, then who should? Why should an external source have so much power and control over what an individual wants to do to themselves exclusively? The comparisons made to drug usage and prostitution are also strange. There’s a focus on the government preventing people from doing things with their bodies, even if they are the only ones affected and are the ones desiring to engage in the activity. With the overturning of the foundation that is Roe v. Wade, the rest of the decisions and provisions resting on top of it are in danger of crashing down.

FDA v. Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine

FDA v. Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine was an appreciated defensive maneuver, declaring that a third party did not have the Article III standing required to challenge the FDA’s relaxed regulations of abortion-aiding drugs and medicine.

While a small victory, the defensive measures around abortion medicine help to keep it a more available resource to those who may need it. The clarification that a third party couldn’t acquire Article III standing makes it infinitely easier to shut down irrelevant anti-abortion parties and individuals from trying to impose restrictions or bans on the medicine.

Medina v. Planned Parenthood South Atlantic

Medina v. Planned Parenthood South Atlantic denied individuals from suing state officials for non-compliance with Medicare’s “any-qualified-provider” provision, specifically in terms of abortion. South Carolina had excluded abortion from Medicare in 2018.

The lack of consequences put on governmental officials for needlessly restricting medical financial assistance for those wanting an abortion sets a bad precedent, simply encouraging the further neglect by government officials of the plight of unwantedly pregnant women and their abortion rights.

The recovery

While the current situation may leave the public feeling unsafe and powerless, there are always resources to reach out to. They’re great places to learn both how to fight against anti-abortion movements and sentiments, and what options and resources women seeking an abortion have.

For those joining the fight

Amnesty International has a dedicated page discussing the issue of abortion rights, exploring many of the societal and cultural nuances that this article doesn’t go into. Their take action page, along with many other causes, also has links to organizations and movements that one may join or follow that directly fight against anti-abortion laws and viewpoints.

Stoponlineidchecks.org brings awareness to the potential for online ID checks to restrict a person’s access to specific information, in this case, abortion. The website’s design itself mimics the annoying and invasive nature of constant ID checks, and provides great advice to those wishing to contribute to the cause against them.

For those in need of assistance

Ineedana.com and Planned Parenthood are both great at providing detailed information regarding the abortion related options and services that a woman has. Ineedana.com serves as a general starting point, helping women find what local services and resources are near them, and what online services and medications are available. Planned Parenthood is great for helping those who wish to get in contact and book appointments with a physician for more information.

The fight continues

The entire history of US federal cases on abortion works well as a roadmap of changing societal viewpoints and the forces working against them by holding on to the past for dear life. They also reveal an unfortunate truth that no protection or regulation can be one hundred percent guaranteed. Much of the progress achieved in forty years has been sliced away in the span of three. However, this lack of guarantee also works as a great double-edged sword. If abortion rights are under constant attack, then anti-abortion sentiments are under just as much heavy fire. The pendulum-like movement between these two groups in terms of legal security and power creates the hope that if people are willing to fight for abortion rights, then they can never be permanently destroyed.

Check Out:

The Impact of GenAI Data Centers on American Communities, and What Can Be Done About It

Be First to Comment